Image: Jerusalem, 1982: My great-uncle, a Kess Wubeshet Aytegeb, is leading the first official Sigd gathering in Jerusalem. Beside him stand President Yitzhak Navon and Chief Rabbi Shlomo Goren.

“And Ezra blessed the Lord, the great God; and all the people answered, Amen, Amen… and fell down before the Lord with their faces to the ground.” -Nehemiah 8:6

When I light a candle for Sigd in my New York apartment each year, those ancient words echo through my living room-not as distant history, but as a declaration:

We are still here.

I didn’t grow up celebrating Sigd.

I was born in Addis Ababa, far from the rural villages where my parents had grown up and where the Beta Israel community observed Sigd with full spiritual force. In their childhoods, it was a day of fasting and pilgrimage. They would wake early, walk for miles up steep hills to gather at sacred sites, face Jerusalem, and listen as the Kesim-our spiritual leaders-recited from the Orit, our Torah written in Ge’ez.

But in Addis, things were different. My parents never told me we were Jewish. They held our identity quietly, carefully-protecting us through silence. I didn’t learn I was Jewish until I was ten years old, when I made Aliyah to Israel.

That was the first time I heard the word Sigd.

Only later did I come to understand just how deeply my family had been part of the holiday’s journey-from exile to arrival, from silence to song.

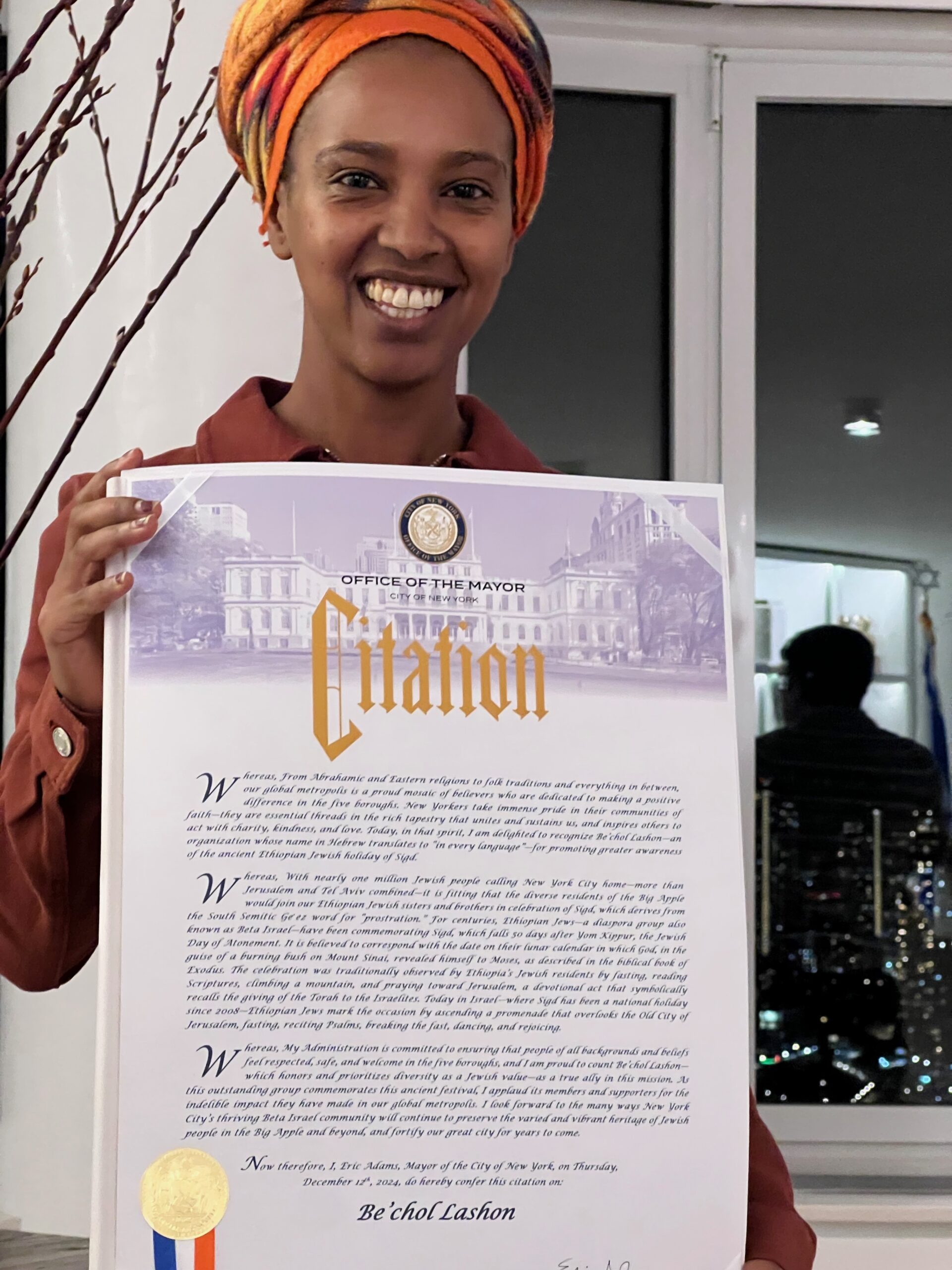

In 1982, the year before I arrived in Israel, my grandfather’s brother-a Kess and community leader-stood at the first public Sigd ceremony in Jerusalem, holding the Orit high before thousands gathered on Mount Zion. In one now-famous photograph, he stands beside President Yitzhak Navon and Chief Rabbi Shlomo Goren, leading the community in prayer. That moment marked the transformation of Sigd from an Ethiopian tradition practiced in quiet exile to a ritual recognized and proclaimed in the heart of Jerusalem.

But my first real experience of Sigd came not from public ceremonies, but from family stories-whispered memories my family carried with them through deserts, camps, and airports. Their longing became my inheritance. Their rituals, my questions.

Today, I live in New York City, raising three daughters. And each year, as Sigd approaches, I feel both deep responsibility and quiet grief.

My daughters know the date. They’ve heard the name. But they don’t yet feel its meaning.

Here, the Beta Israel community is scattered. There is no Kes to guide us, no shared synagogue or gathering space. Unlike my parents, who live in Montreal and are part of a small but resilient Beta Israel community that celebrates Sigd together, we are alone in our observance.

Still, I try.

Each year, we light a candle. We sit at our table. I tell them the story of Ezra-how the people, newly returned from exile, gathered to recommit themselves to Torah. We write short intentions or confessions, and sometimes we sit in silence. I show them the photo of their great-great-uncle on that Jerusalem hilltop, and I tell them: This is part of you.

They listen, but the connection still feels fragile. Without peers, without space, without the rhythm of community, I worry that the story won’t hold.

Sigd (from the Ge’ez word for “prostration” or “worship”) is often called the “Ethiopian Yom Kippur,” but it is more than that. It’s about return-not just to God, but to one another. It’s our Mount Sinai moment, when we gather as a people to reaffirm the covenant and face toward Jerusalem with humility and hope.

For centuries in Ethiopia, Sigd anchored the Beta Israel community-spiritually and socially. It was a ritual of resistance, a declaration of continuity in the face of distance, persecution, and invisibility. Our people kept Sigd alive long before anyone outside our community recognized it.

In 2008, the Israeli government finally declared Sigd a national holiday, thanks in large part to the voices of leaders like my great-uncle and the perseverance of younger generations born into exile. And yet, even in Israel, many still don’t know what Sigd is, or why it matters.

After October 7, I’ve felt a different urgency when I speak to my daughters about our history.

As antisemitism rises, as Jews around the world feel more vulnerable, I understand Sigd not just as tradition, but as spiritual armor. A ritual that has carried our people through wilderness before.

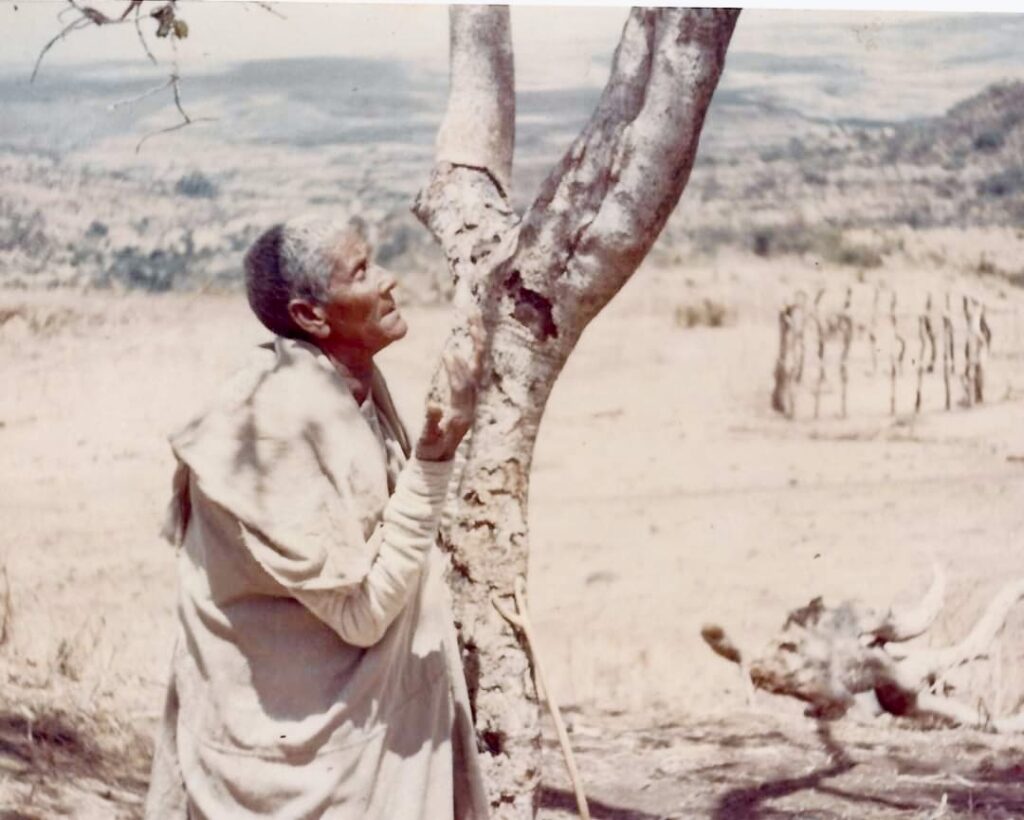

I think of my parents walking to the hilltop. I think of my great-grandmother in white, bowing low under a tree in Ethiopia. I think of my great-uncle, lifting the Orit in front of a nation. And I think of myself-just a mother with a candle, trying to hold onto something sacred in a world moving too fast.

Ambober, Ethiopia, 1956: My great-grandmother praying during Sigd in Ambober, Ethiopia.

There’s a rhythm to Sigd: fasting and climbing, confessing and blessing, silence and song. In Ethiopia, that rhythm was lived with the whole body. Now, in my home, it’s lived in fragments-in words, in rituals improvised and quiet, but still meaningful.

Sigd teaches that return is always possible. That silence can hold memory. That even in diaspora, even in isolation, we are not erased.

One day, I hope my daughters will lead their own rituals. I hope they’ll remember these candles, this table, this quiet attempt to pass something down. I hope they’ll feel Sigd not as a story they were told, but as a birthright they embody.

Until then, I’ll keep lighting the flame. I’ll keep telling the story. And I’ll keep whispering into the quiet:

We are still here.

Wishing you a happy and meaningful Sigd.

Glossary

- Beta Israel: The historic Ethiopian Jewish community.

- Sigd: A holiday observed by Beta Israel 50 days after Yom Kippur to reaffirm commitment to the covenant and Torah.

- Kes/Kessim: Spiritual leaders (priests) in the Ethiopian Jewish tradition.

- Orit: The sacred text of Beta Israel, written in Ge’ez, including the Five Books of Moses and other scriptures.

- Ge’ez: Ancient liturgical language used in Ethiopian Jewish religious life.