I never expected to find myself celebrating the end of Shabbat on a crowded strip of park between the Han River and the posh Gangnam neighborhood of Seoul. Yet this summer as the sun set, the familiar words and tunes of the Havdallah service made me feel at home in a place that was vastly different than any I had ever been.

I traveled to South Korea at the invitation of Souks Soukhaseum, a Loatian American who spent Shabbat with the local Jewish community, Hakehillah Korea. In my work for Be’chol Lashon, I often teach that there are Jews on every continent. This was my first chance to see Asian Jewish life in action. I was there to participate in a special Shabbat gathering and to consult and support this fledgling community. (This was one of many regional gatherings that Asia Progressive Judaism, APJ was helping to coordinate.)

It is estimated that among the over 51 million people in South Korea, there are no more than 1,000 Jews. Most of these Jews are immigrants to or sojourners in South Korea. There is no permanent synagogue or kosher market. Yet, it is here that a group of Jews have sought each other out.

Anna Yun originally came to South Korea in 2009 to teach English. She grew up in Minnesota, and her interfaith family “was an original observer of Chrismukkah long before it was cool.” Tamar Godel also came to South Korea to teach English. Abraham Kanter is one of the many Americans working for the American government in South Korea. Like Yun and Godel, he came without any intention of looking for Jewish community.

Yun attended a Christian college, and her sister is a Christian theologian. But as she grew into adulthood she found herself identifying more and more with her Jewish heritage. As she explains, “There is something powerful about the stories we tell that get passed down from generation to generation and how they are not set in stone. We can continually analyze these stories as we go. We are not bound by national boundaries, race, or gender either. Whether or not some would like to admit it, we are so incredibly diverse even among ourselves, and this gives us the power to adapt and evolve with time.”

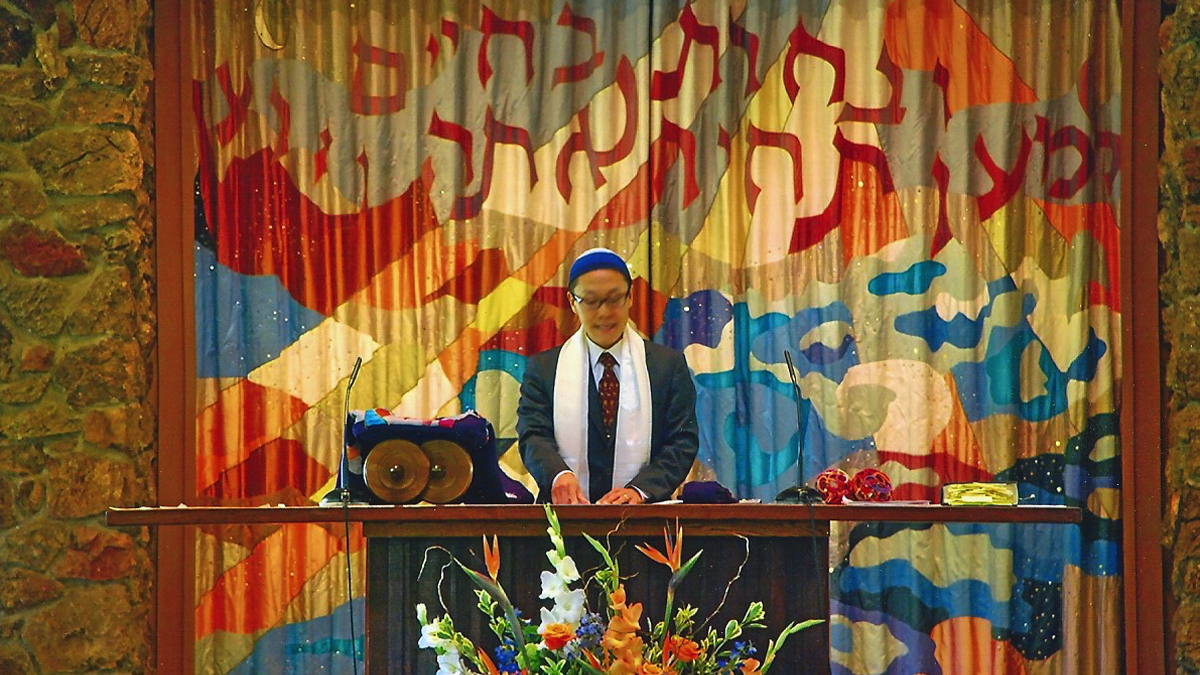

Participants in Hakehillah Korea’s Shabbat gathering at Gyeongbokgung Palace: (left to right) Hangu Yun, Anna Yun, Tamar Godel, Adam Krongold, Rabbi Ruth Abusch-Magder, Rabbi Nathan Alfred, Souks Soukhaseum, Laurie Chow Kanter, and Abraham Kanter. (Ruth Abusch-Magder)

For Yun, who has made a permanent home in Korea, assimilating into Korean society has changed her relationship to Judaism. As she explains, “Koreans have a strong sense of shared history and culture, and that has definitely caused me to feel more strongly that I need to understand what Judaism means to my own identity. Fully assimilating as a white person in Korea is impossible, but there is a lot of my identity that has changed during this journey so that I can fit in better. As parts of my American identity have faded away, I realized that my Jewish identity is something that I valued deeply and couldn’t just let go of for convenience.”

Godel comes from a deeply connected Jewish family. Her grandfather was a rabbi, and much of her youth and young adult life was spent in Philadelphia in deep connection with the institutions and rhythms of Jewish life. By contrast, she says there is very little understanding of what Judaism is or what it means to be Jewish in Korea. “Many of my students don’t really understand what a religion is at all, let alone one that isn’t church-based,” Godel explains. She is hoping that Hakehillah Korea will allow her to access some of the elements of Jewish life she misses from home, such as “shabbat dinner, Hanukkah parties, and Passover seders, etc.”

As a child, Kanter attended a traditional yeshiva day school. He is no longer religious today but became involved with Hakehillah Korea because he “enjoys the others in the group, especially because they don’t take the religion way too seriously.”

Like the havdalah service, most of Hakehilla Korea’s gatherings have been social in focus with elements of tradition thrown in. Food is a big draw. It is hard to find western style bread in Korea, so the promise of challah always brings people together. At Hanukkah, the latkes were a big hit. Even the high holy days focus more on food than prayer, a picnic for Rosh Hashanah and a meal in the sukkah for Sukkot.

Starting small but dreaming big, Hakehillah Korea is selling Jewish Korean calendars that will help fund activities and get the word out about Jewish life in Seoul. Yun says she hopes to be able to overcome some of the obstacles to living a rich Jewish life by coming together and being able to be “in community with other Jews when it comes to holidays and Shabbat.” After all, as she explains, there are some strong similarities between the Korean and Jewish cultures: “The obsession with food and meals, a history of surviving despite great obstacles, the oddly similar literary traditions and themes, and the large diaspora communities.”

Though the gathering I attended this past summer was small, the vibrancy and passion of those involved was impressive and provided a bridge between cultures. Without a kosher market, vegan foods were provided for those who keep kosher -including a fully vegan kosher kimchi and homemade challah. Over the weekend we visited the palace, learned about Korean history and got to try on traditional Korean outfits. We saw the traditional historic neighborhoods as well as the ultra modern skyscrapers that fill the skyline. On Shabbat morning, we improvised a Torah reading. Drawing on his Talmud Torah days, Kanter was able to sight chant the weekly reading using a chopstick for a yad. Given the enthusiasm with which his toddler daughter to followed along, there is every reason to believe that Judaism in Korea can find a way to thrive.