As a Jewish-German-Colombian-New York artist, Julian Voloj is both one of a kind and very at home in the world of comic books. Through comics, he has explored identity and forged community in navigating the overlap between his Jewish and Latinx experiences and expression. He has participated in specific Jewish and Latinx comic shows, and yet these two elements have never come together—until now. In celebration of National Hispanic Heritage Month, Voloj, a Be’chol Lashon staffer, arranged Convivo, an art exhibition about Jews, Hispanics, and comics in partnership with Jewish Art Salon, Bronx Heroes Comic Con, and Repair The World.

Voloj spoke with the two curators, Joel Silverstein, a founding member of the Jewish Art Salon, and Ray Felix, an arts educator and founder of Bronx Heroes Comic Con, about their vision for Convivo and the world of comics more generally.

Thank you, Joel and Ray. It was wonderful to work with you both to organize Convivio. Can you tell us your thoughts about the exhibition?

Joel Silverstein: It began on a meditation on Convivencia, the storied and hallowed era of Jewish, Catholic and Muslim cooperation centered in Spain in the early Middle Ages. Although this era of fabled goodwill is historically hotly contested and debated, it is an idea that is seductive, positive and hopeful.

In real terms, the exhibition spoke to me because of my 18 years as a NYC DOE high school art teacher and artist, centered on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Delancey Street is the quintessential Jewish neighborhood in the early 20th century, but it was also shared for the last sixty years with Hispanics, primarily Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, Mexicans and others. The relationship between the two groups was complex yet complementary.

Jews began the comic book industry in the 1930s and 40s, and by the 1970s and 80s Hispanics entered into the field. They saw comics as a way to create an artistic identity. In many ways, the two groups paralleled each other.

How did you get involved in comics?

Ray Felix: I’ve always been attracted to comics since I was young. My father, who was in the Air Force Reserves, returned home from Germany and Spain and brought my brother and me stacks of comics tied with twine. There was the Flash, Batman and Superman. I think since that moment I was attracted to the comic medium.

When I was a kid, I wasn’t a geek or a nerd because I read comics. As a kid, me and my friends worked out, exercised and fought in the streets of the Bronx. We wanted to be the heroes and we wanted to look like them as well. Growing up in the Bronx, in retrospect, was traumatic. I fought in school, I fought in my neighborhood, and if I lost a fight my father would make me fight the kid again with boxing gloves in the backyard. So yes, I identified with the mean streets of the Bronx and with Gotham City, where Batman fought crime, and Hell’s Kitchen, where Daredevil fought. I wasn’t concerned about looking for a character that identified with my Latino culture or ethnicity. All kids wanted to be associated with the fight culture, and we aspired to be gladiators of the streets.

Silverstein: I have been passionately involved with comics since I was a boy. Part of my interest sees the mythology of comics as a secularization of religious thought and specifically Jewish religious thought. My tastes were eclectic. I loved Superman and Batman, Tarzan, Conan the Barbarian, Swamp Thing, Captain America, Horror Comics, The Spirit by the great Will Eisner and of course my art god, Jack Kirby, especially The Fourth World, The Demon, and Kamandi. I loved superheroes, but I really loved the off-beat, second-banana characters.

As I show in my new book Joe Shuster: The Artist Behind Superman, many of the pioneers of the American comic book industry were Jewish. However, their Jewish identity was often a taboo topic. Why do you think this was?

Silverstein: That was really true in a way that we as contemporary Jews can’t really comprehend. Jews changed their names and their identities to get business. The comic book industry was the rag trade of the publishing world, and this was the only place Jews could crash. They were unfairly barred from advertising, high-end magazines, etc.

Many have written about how aspects of Superman, like his name, origin etc. seem Jewish. It’s not a surprise given the Jewish immigration and assimilation experience. In an era after [Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel] Maus and The Rabbi’s Cat [by French comic book artist Joann Sfar], Jews are very free to write and draw graphic novels or indie comics centering on identity. There is no shortage or lack of interest. Yet I feel that there is still a glass ceiling on Jewish identity in mainstream comics.

Ray, do you think that Latinx comic creators are able to be open about identity in their work today?

Felix: It has been my experience that no one wants to hear the Latino perspective in comics. Since the Latinx movement, there are some small strides being made, but we are divided among ourselves as well. I was criticized once as being “not a real Latino” because I don’t speak Spanish. My comment back was that speaking Spanish is no different from speaking English because they are both the language of our colonizers and not of our native people.

In the past, mainstream comics were often all-American with white male heroes. Now there is more diversity in mainstream comics. What changed? And how important is representation?

Silverstein: I think the great thing about now is that diversity is a given. It used to be an unfulfilled need and a secret. Now it can be out in the open. And by giving people heroes of all sorts, you are not just helping the group who is being depicted. You are helping people in the mainstream who never gave it a thought that other kinds of heroes were possible. Convivio is the kind of show that should be done because not only do Hispanic Jews exist, but Jews and Hispanics have shared New York neighborhoods (the Lower East Side, the Bronx) and have parallel histories as outsiders to the mainstream Anglo culture.

Felix: Growing up, there were no comic heroes that looked like me, so when I became an indie comic book artist, I created my own heroes. However, I never felt left out of comics as far as identity is concerned because I never needed a comic book to make me feel included.

The only reason why [major comic book companies] are now becoming more diverse is because they’re losing their core audience. Diversity is great in comics and I love it, but I believe that large companies are mainly motivated by financial gain, not by inclusion.

Tell us about the artists in the show? Can you highlight a few pieces and tell us why you selected them for the show?

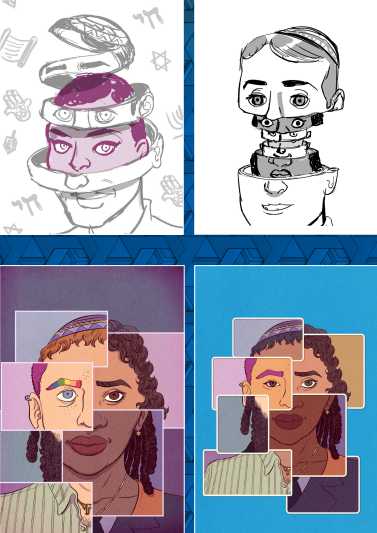

Silverstein: All the works in the show demonstrate aspects of Jewish and/or Hispanic identity, or showcase the role of Jews and Hispanics working in the comic book industry. The artworks also show the nature of these respective cultures, how they have impacted and changed over time and more importantly, what they have learned from each other. Noaj Sauer is an Argentine Jew who has created banners dedicated to gay identity in the Hispanic Jewish community. Miguel Trelles is a Cuban/Puerto Rican painter who creates works highlighting pop culture, in this case the fantasy illustrator Frank Frazetta and Mayan drawings, thus highlighting issues of colonialism, racism, masculinity, and American patriotism. Archie Rand created a series based on the bombed-out cities of post-war Germany after the Jews were hauled away.

Felix: We have Jose Luis Garcia Lopez, who gave us a fresh look from the Curt Swan style DC was known for for decades. N.Steven Harris and Grant Morrison created a Latin superhero named Aztec, made him a doctor and broke negative stereotypes of Hispanics as gangsters with bandanas and pipes. Sara Wooley and Laura Alvarez use the comic book medium to tell personal stories about their experiences and their families’ heritage.

And you both have pieces in the show. Can you tell us about them?

Silverstein: My own work fuses superhero and Jewish imagery in expressionist paintings. In “Hulk Meets Samson,” I copied Peter Paul Rubens’ painting “Samson and Delilah” and mixed it with Lou Ferrigno’s Hulk. Both heroes are portrayed as Jewish protagonists.

Felix: “The Roach” is a Puerto Rican superhero as a bug. It’s inspired by a childhood experience. Every time a tenant moved out, my brother and I had to fumigate the roaches that they’d bring with them. I exterminated literally thousands of roaches, ants and water bugs growing up. As an adult, I began to think about how that must affect my karma in the wheel of life. So I wrote a story about karma and becoming the Roach. It’s actually a parody on Gregor Samsa from Kafka’s Metamorphosis.

And what about your pieces in the show, Julian?

Thanks for asking. We are including a page from my 2015 non-fiction graphic novel Ghetto Brother (illustrated by Claudia Ahlering), which focuses on the life and legacy of Benjamin Melendez, a Puerto Rican gang leader who brokered a truce that paved the way for hip-hop in the Bronx. The page we’re featuring in the show deals with Melendez’s family secret: His parents were Crypto-Jews, and this discovery leads later in the story to his own exploration and reclaiming of his Jewish identity.