I think about the nature and concept of forgiveness literally on a daily basis. As a lawyer, my practice consists solely of defending persons facing the death penalty; my clients are either facing the death penalty at trial or they have already been convicted and are in the state appeals process. Persons on the outside would be astonished to learn how much justice, forgiveness and peace color the many decisions my clients make that impact their future.

At some point after a death penalty trial is over, but before pronouncement of sentence, the accused have the right to make a statement; to allocate to the court, jury, and gallery. During these statements, I have never had a client asked to be spared. The lawyers ask for it, families weep for it, but my clients do not. For the first time in a long process they get to speak freely and they use this time to say, “I am so sorry.” They blame no one, and offer no excuses. They believe in their heart of hearts that Justice requires their life in return for the one(s) they have taken.

Rabbi Milton Steinberg once wrote that “the upshot of the Jewish teaching on what I owe my fellows: I owe them the right, the just, the equitable.” I represented a man who was implicated in a double homicide that occurred 25 prior to his arrest for it. He spent that time of his life in a haze of drugs and alcohol. But one thing he maintained was that if he did those things he deserved to die. For him, the only way he could atone was to give his life in return. He was one of many persons I have met that are willing to give their life in return for the one they took. In other words, they too strive to give what they believe they owe their fellows.

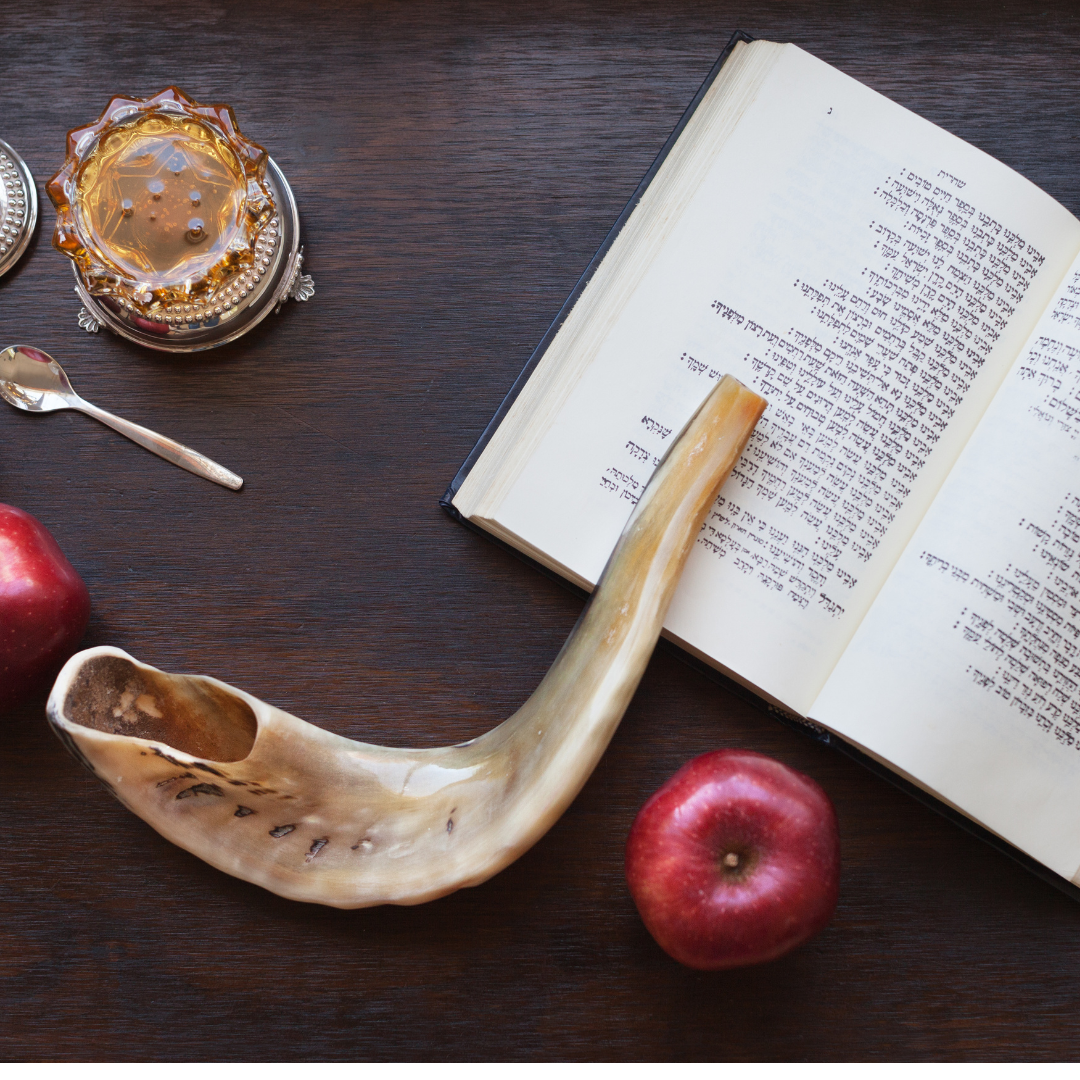

As we approach the Yom Kippur, this year as in previous years, I think about lessons learned from the people I encounter in my line of work, killers and victims alike. I recall a mother looking at my client and saying with conviction, “I forgive you,” and that client breaking down and saying over and over, “thank you”; I think about the father who looked at one client and said, “I pray every day to find a way to forgive you, but I’m not there yet” and that client nodding his head in understanding; I think about the mother who looks at yet another client and says, “ I will never forgive you”, and he flinched as if struck. For one man, the gift of forgiveness; for the other, the hope of forgiveness; for one the despair of forgiveness denied.

My clients have also displayed an amazing capacity to forgive. To forgive the mother for turning tricks in front of them, to forgive the father for brutal beatings, to forgive the rapes; the tortures; the things no child should have to endure. Those clients who look at me and say “what I did is not their fault”; “she is still my mother and I love her”; “she had it rough, I understand.”

I once asked my rabbi, “how can you tell when you have forgiven someone”? and he told me, “when you can begin repairing the relationship.” So, when I look around a court room and death as a sentence is on the table, I see mothers who have never been at the side of their child before this time—are now standing there beside them. They are standing there with full understanding that the world knows about their faults, their failures, their transgressions against their child; and yet, they are there. When they get a turn to speak, they ask for forgiveness: they turn to my client and ask for forgiveness; they turn to the victim’s family as ask for forgiveness; and they turn to the jury and ask for mercy. I see the transformative power of justice and forgiveness. When you have those two, peace is sure to follow.

I once met a man named Billy Moore. Billy spent 24 years on Georgia’s death row for a crime he freely admits to committing. Immediately after the murder during a robbery gone bad, Billy was so eaten up by remorse he confessed, led the police to the murder weapon, and the meager proceeds of the robbery. Despite his sincere regret and remorse, he was sentenced to death. While on death row, he wrote to his victim’s family expressing his sorrow and apologies. The family had compassion and forgave him; and they wrote each other for over 16 years. That family was instrumental in getting Billy’s death sentence commuted to life and ultimately led to his parole.

When I met Billy, I was struggling with my own inability to forgive a loved one’s bad decision that indirectly led to my grandson facing many years in prison. Billy told me something I will never forget. He said, “you have to remember forgiveness is not for the other person, it is for you. Forgiveness sets you free to find peace. You must not forever link your grandson to another’s failures. You must love him independent, look at him and see love, not another’s mistakes. When you look at him and see only him, you will know peace.”

So as I struggle, I remember a promise: “Insomuch as ye have come before me in judgment and departed from me in peace, I do reckon it unto you as if ye have been created anew.” I’m working on it, but I’m not there yet. Shalom.