At Passover, families come together to celebrate an ancient, shared tradition, encouraging people of all backgrounds and faiths to sit down and eat together. Some seders place Ashkenazi, Sephardi and Mizrahi foods and rituals side by side; for multiracial and multicultural Jewish families, the Passover seder is an opportunity to share elements of their racial and cultural backgrounds. No matter their traditions, one thing all seders have in common is that families and friends around the world share matzah, make memories and celebrate the diversity of the Jewish people. [vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1616467405280{margin-top: 10px !important;}”]  As an African-American and a Jew by choice, Marcella White Campbell can’t help drawing parallels between the Passover seder and Thanksgiving. In both cases, tradition brings family and friends around a table for a festive meal. When Marcella and her husband Greg hosted their first seder, they included Greg’s white, Ashkenazi Jewish extended family as well as Marcella’s black, non-Jewish extended family.

As an African-American and a Jew by choice, Marcella White Campbell can’t help drawing parallels between the Passover seder and Thanksgiving. In both cases, tradition brings family and friends around a table for a festive meal. When Marcella and her husband Greg hosted their first seder, they included Greg’s white, Ashkenazi Jewish extended family as well as Marcella’s black, non-Jewish extended family.

“Passover is all about asking and answering questions,” Marcella says, “so it was the perfect opportunity for my side of the family to learn about Jewish history and tradition, and a great way to bring both families together.”

It was such a success that Passover has replaced Thanksgiving as the event of the year for Marcella’s family, too. “For both sides of our family, Passover is the one time of year we all come together.” [vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1616467410579{margin-top: 10px !important;}”]  Helen Kim and Noah Leavitt, co-authors of JewAsian, are married to each other and living their own JewAsian lives. When it comes to Passover, Helen, a Korean Jew by choice, loves to celebrate the traditions that Noah grew up with, though they do add rice in with a nod to Korean culture. Like many Jews, each year they add in supplemental materials to help keep the Exodus story relevant. [vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1616467416239{margin-top: 10px !important;}”]

Helen Kim and Noah Leavitt, co-authors of JewAsian, are married to each other and living their own JewAsian lives. When it comes to Passover, Helen, a Korean Jew by choice, loves to celebrate the traditions that Noah grew up with, though they do add rice in with a nod to Korean culture. Like many Jews, each year they add in supplemental materials to help keep the Exodus story relevant. [vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1616467416239{margin-top: 10px !important;}”]  Davi Cheng uses her art to blend her Asian heritage with her Jewish identity, as she did in designing a stained glass window for her synagogue that includes waves inspired by Japanese images, or in her depiction of the people of Israel as Chinese characters crossing the parted sea. Even if Davi and her wife Bracha are not hosting their own seder, Davi still finds ways to incorporate elements of her Chinese identity and experience. During dinner conversation and discussion, she often shares stories of her parents fleeing China, drawing parallels with the story of Exodus. [vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1616467430600{margin-top: 10px !important;}”]

Davi Cheng uses her art to blend her Asian heritage with her Jewish identity, as she did in designing a stained glass window for her synagogue that includes waves inspired by Japanese images, or in her depiction of the people of Israel as Chinese characters crossing the parted sea. Even if Davi and her wife Bracha are not hosting their own seder, Davi still finds ways to incorporate elements of her Chinese identity and experience. During dinner conversation and discussion, she often shares stories of her parents fleeing China, drawing parallels with the story of Exodus. [vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1616467430600{margin-top: 10px !important;}”]  At Jennifer Stempel’s seder, the retelling of the Exodus story resonates strongly with the experiences of her Cuban-American family. As the biblical drama unfolds, Stempel explains, “we spend a lot of time talking about what freedom means and what our family sacrificed for the chance at freedom. It is often the time when we retell and reflect on our own story and journey.” [vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1616467436367{margin-top: 10px !important;}”]

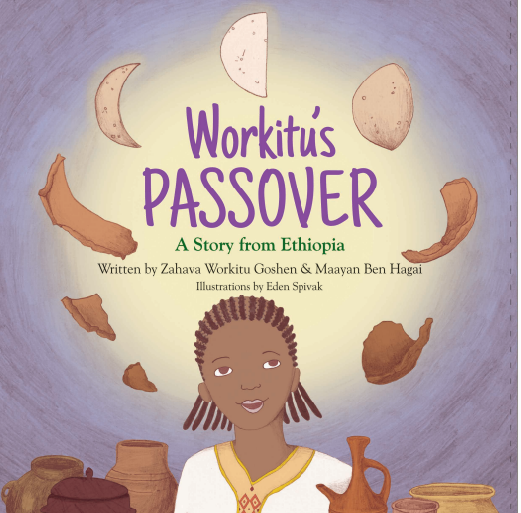

At Jennifer Stempel’s seder, the retelling of the Exodus story resonates strongly with the experiences of her Cuban-American family. As the biblical drama unfolds, Stempel explains, “we spend a lot of time talking about what freedom means and what our family sacrificed for the chance at freedom. It is often the time when we retell and reflect on our own story and journey.” [vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1616467436367{margin-top: 10px !important;}”]  Some Jews recount the personal stories of their own escape as part of the seder. Avishai Mekonen explains, “In 1984 when I was 10 years old, my family escaped from Ethiopia and walked 400 miles to Sudan.” Avishai and his wife Shari made the documentary, 400 Miles to Freedom, about his journey: “Telling the story of my own Exodus helps my children connect to their Ethiopian heritage. Our motivation as filmmakers revolves around the power of personal stories to enlighten and to heal.” [vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1616467441601{margin-top: 10px !important;}”]

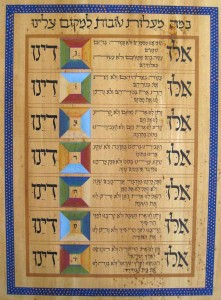

Some Jews recount the personal stories of their own escape as part of the seder. Avishai Mekonen explains, “In 1984 when I was 10 years old, my family escaped from Ethiopia and walked 400 miles to Sudan.” Avishai and his wife Shari made the documentary, 400 Miles to Freedom, about his journey: “Telling the story of my own Exodus helps my children connect to their Ethiopian heritage. Our motivation as filmmakers revolves around the power of personal stories to enlighten and to heal.” [vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1616467441601{margin-top: 10px !important;}”]  Much of Rabbi Mona Alfi’s family are Persian Jews. Many cultural and linguistic elements—American, Iranian, Jewish—exist side by side at her family’s seders. Her father conducted the entire seder in three languages: “In Farsi, so the older generation understood, in English so the younger generation understood, and in Hebrew for God, which made for a very long seder.” [vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1616467446606{margin-top: 10px !important;}”]

Much of Rabbi Mona Alfi’s family are Persian Jews. Many cultural and linguistic elements—American, Iranian, Jewish—exist side by side at her family’s seders. Her father conducted the entire seder in three languages: “In Farsi, so the older generation understood, in English so the younger generation understood, and in Hebrew for God, which made for a very long seder.” [vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1616467446606{margin-top: 10px !important;}”]  For Adam Kofinas’ Greek family, unfamiliar foods initially caused some confusion on both sides: “My mom and her parents were invited to my dad’s family seder, replete with Greek tunes and customs. Out came the meal, and my maternal grandmother was shocked and confused to see what looked like mini extra well-done hamburgers. Little did she realize that these were leek patties, something that she would enjoy for years to come. Fast forward 25 years to our family seder, replete with both Greek and Ashkenazi trimmings. Sure enough, when we went to serve the matzah ball soup, members of my Greek family looked puzzled and asked what it was, a food with which they were unfamiliar.”

For Adam Kofinas’ Greek family, unfamiliar foods initially caused some confusion on both sides: “My mom and her parents were invited to my dad’s family seder, replete with Greek tunes and customs. Out came the meal, and my maternal grandmother was shocked and confused to see what looked like mini extra well-done hamburgers. Little did she realize that these were leek patties, something that she would enjoy for years to come. Fast forward 25 years to our family seder, replete with both Greek and Ashkenazi trimmings. Sure enough, when we went to serve the matzah ball soup, members of my Greek family looked puzzled and asked what it was, a food with which they were unfamiliar.”

But today, both sides happily eat each other’s foods and enjoy seder together.