“Is that the flag of Turkmenistan?”

As my ride was pulling up, the bold green flag with a red rug-like stripe, affixed to the fender, proudly charged forward.

The driver glanced at me through the rearview mirror. “Yes, you know Turkmenistan?” he asked, surprised.

“I’ve heard of it, but I don’t know much,” I admitted. The extent of my knowledge was limited to high school map quizzes and online flag tests.

Our eyes met again in the mirror. “Are you Arab?”

“Not really…” I hesitated, my words hanging. “My family was from Syria and Libya many years ago”, I added. “Bas adrus al–‘arabiyyeh”—but I’m studying Arabic.

Seemingly satisfied with my answer, he stated, “Turkmen comes from Turk and Imaan. You know what that means?”

It was as if he flipped a buried switch. Without thinking, I instinctively volleyed back, “Believer.”

“Yes, people from the Turk nation who accepted Islam.”

Trying to gauge his reaction, I asked, “Was that used for all nas al-kitaab—all people of the book—or just Muslims?”

I studied his face while he kept his eyes on the road. He seemed unbothered by the question and started to explain the history: how Turkic groups moved from Mongolia to Central Asia, how the Persian empire influenced the language, and how Islam spread through the tribes.

The conversation flowed and progressed smoothly, but something in me was still stirring. I hadn’t been entirely honest with him. My silent secret started inflating inside me, building internal pressure with each passing sentence. I shifted in my seat, weighing my options, then chose to reveal a secret, unsure how he would react.

“I’m Jewish.”

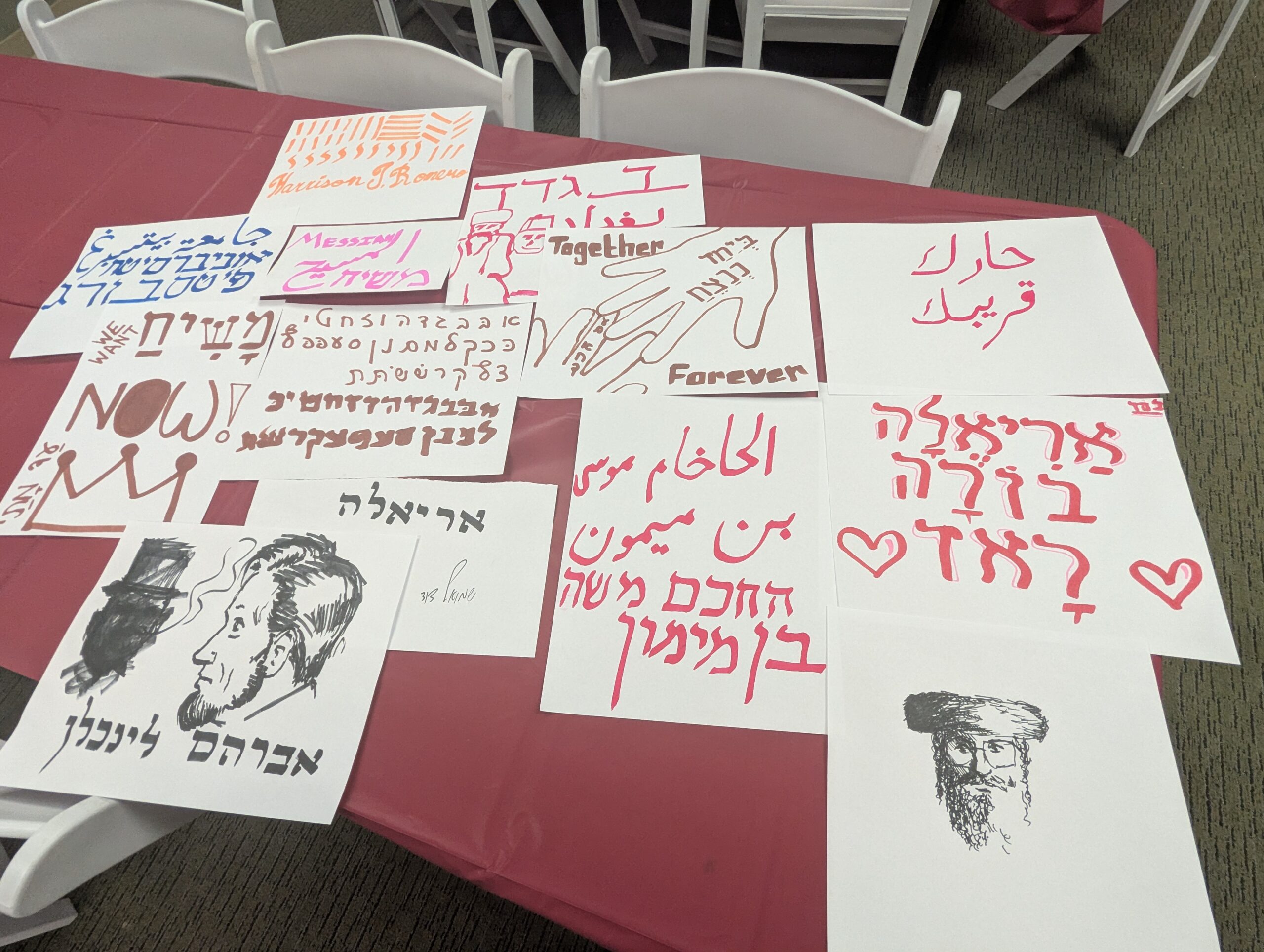

The silence I expected arrived and I started to question myself. However, as quickly as it came, it went. Without any further hesitation, he said, “Jews are People of the Book! Ahl al-kitaab,” and started a conversation over cognates between Hebrew, Arabic, Persian, and Turkmen; the criteria Hakim Musa ibn Maimoun (the Rambam) laid out for identifying the messiah; and our shared confusion at the Catholic holy trinity and transubstantiation.

Retrospectively, my reluctance to share my identity might seem paranoid. However, the flames of antisemitism were rekindled near and far following the October 7th terror attacks. Jewish individuals and institutions ranged from Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom, to my community in Pittsburgh. My friends were assaulted on campus for being visibly Jewish, religious and cultural buildings were defaced with graffiti, and Israelis were instructed to “go back to Europe” following chants of “min al-mayeh l-al-mayeh, filasteen ‘arabiyeh—from the [river] to the [sea], Palestine is Arab.” There were even calls to “globalize the Intifada,” the word used for waves of riots and attacks that targeted the military and civilians alike.

These chants that rang throughout campus had a deeper resonance. My European ancestry was clearly unwelcome: neither my great-grandfather, who found refuge in Israel following the Holocaust nor the branch of my family that made aliyah six generations ago (then, the Ottoman Empire) had a place in the narrative. My “Arab” side found no refuge either. My Tripolitanian grandfather, a Libyan-born Arabic-speaking lawyer, leveraged his identity to advocate for his Palestinian clients. He was attacked in the very Intifada that my fellow students now glorify. Even my twelve generations-long roots in the Land of Israel (which trace back to Syria) have not protected me from accusations of being a colonizer. The connection between my Jewish heritage and the outside world never felt more tense.

In deliberate efforts to resolve that tension, I began taking steps to understand how my different identities fit in with each other. I started exploring Arabic through university courses to not only deepen my language skills but also reconnect with my Arabophone heritage. I also joined the American Sephardi Federation’s Sephardi House Fellowship with the hopes of bringing events celebrating the legacy and culture of Middle Eastern and North African Jews to a campus that was predominantly Ashkenazi. However, the Fellowship gave me more than that.

Through learning and discussion sessions, my cohort explored the vast interactions Jews had in the Middle East, ranging from day-to-day coexistence to leadership under Islamic regimes, and even forced expulsions and mass killings. Shabbatons in New York City and Miami connected me with fellow fellows, who have been leading efforts on their own campuses to tell the untold stories of their ancestors. With support and resources from ASF, I was also able to bring programming to campus that highlighted the lesser-known history of Sephardi Jews, narrated through cuisine, art, and family stories.

Through this year-long journey, I found clarity and pride in my multi-layered Jewish identity. I realized that I am not divided by my identities; instead, I am a product of them.