As we move towards the 54th anniversary of Loving v. Virginia, the landmark Supreme Court ruling that legalized interracial marriage across the United States, I’m consistently reminded that, throughout American history, the fortunes of the multicultural and multiethnic family have been inextricably linked to legal definitions of race. Hundreds of thousands of Americans have died to expand or maintain the boundaries of who is and who is not a person, who can and who cannot marry, and, thus, whose family is and is not legitimate.

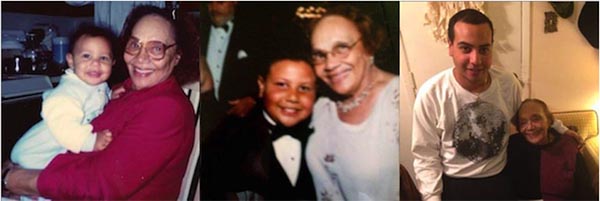

My own family is a multiracial Jewish family who lives at the intersection of Black and Jewish. Throughout American history, families like mine have been ignored, overlooked, persecuted, and outright illegal.

Nevertheless, I have always sensed that my Jewish family’s story was a universal Jewish story. I have told that story to skeptics who believe we Jews with diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds are statistically insignificant; to others who believe we should wait until our numbers reach some hypothetical tipping point before demanding representation, access, and resources; and, sometimes, to my own children when the pressure of being an “only” has discouraged them.

Our family, I tell them, is both unique and commonplace. We don’t need numbers to prove our worth.

American Jewish adults under 30 are the most diverse of any living generation. (Graphic by Laura E. Adkins for the Forward; data from Pew Research Center’s “American Jews in 2020” report)

That being said, I am pleased to see that the new Pew 2020 study has found that the US Jewish population, along with the country’s population as a whole, is growing more racially and ethnically diverse. Most striking is the pattern of rising diversity for adult Jews under age 30: 15% identify as ethnically and racially diverse (7% Hispanic, 2% Black and 6% Mixed-race), double the percentage for Jewish adults over 30.

Unlike the last Pew survey in 2013, the 2020 survey also asked about the race and ethnicity of other adults and children in Jewish households. The data indicate that 17% of U.S. Jews live in households where at least one person — adult or child — is Hispanic, Black, Asian, another (non-White) race or ethnicity, or multiracial; this includes household members who may not be Jewish. The Jewish American family is more diverse than it has ever been.

For my family, as for the families and young people that Be’chol Lashon serves, this continues to be an everyday reality. In 2018, Pew reported that millennials were more diverse than previous generations, but diversity is increasing. Nearly half (48%) of Generation Z, who are currently between the ages of 6 and 21, are multiracial. Jews are part of American life and are affected by national trends. Whether through birth, intermarriage, conversion or adoption, Jews are a diverse people, Jewish families are diverse, and race and ethnicity are important elements in shaping Jewish identity and expression.

To keep pace with these changes, research methodologies must continue to evolve. Be’chol Lashon, where I am executive director, grew out of concerns about the accuracy and efficacy of contemporary Jewish demography — particularly with regards to Jewish diversity. In fact, Be’chol Lashon was founded in 2000 in response to The Study of Ethnic & Racial Diversity of the Jewish Community, the first of its kind. At the time, demographers sourced Jews by pulling from lists of people who were determined to have “distinctive Jewish last names”, called DJNs. It is immediately apparent to even the casual observer that such methods would have excluded wide swaths of the Jewish community; however, even contemporary methods are behind the curve.

When Pew conducted its 2013 survey, demographers selected a sample size of Jews by calling randomly selected phone numbers and asking respondents if they were Jewish. By 2020, however, response rates to these telephone surveys had declined, so researchers sent letters to randomly selected residential addresses across the country, asking the recipients to submit a short screening survey online or by mail. Given how difficult it is to find a significant sample size of people who identify as Jewish, it is even more challenging to find people who identify as Jews of Color. Research methodologies must continue to evolve to accurately count us.

In addition, as numbers of multiracial and multiethnic couples and children continue to rise, a growing number of Americans are finding it difficult to select a single racial or ethnic group in surveys and on census forms. We can only speculate what surveys like Pew or the census will look like in the future, but racial and ethnic categories will likely be very different from those on the 2020 Pew or Census questionnaires.

Despite overall declines in traditional Jewish engagement, 94% of Jews expressed pride in their heritage. Meanwhile, previous studies have shown that diversity and inclusion are important values for young Jews and a key lens through which they make choices about engaging in Jewish life. Jews at the “margins,” or, more accurately, at the “frontiers” of Jewish life, are looking for ways to engage. They find meaning and relevance in a Jewish community that holds space for ethnically and racially diverse Jews. Multiethnic Jewish families deserve a Jewish community that validates them, supports them — and counts them.