Growing up in San Francisco, Rabbi Jacqueline Mates-Muchin and her siblings went to Hebrew school to learn about Jewish traditions, and to Chinese school and summer camps in the city’s Chinatown. She rarely experienced the feelings of doubt that she has helped many young Jews of Color (like myself) overcome. Nor did the first Chinese-American rabbi and the senior rabbi at Temple Sinai in Oakland, CA ever think she couldn’t be a rabbi because of her dual identities.

“I didn’t feel like there was a push or pull [of identities],” she shared in an interview for LUNAR: The Jewish-Asian Film Project. “I think my parents had a really good approach to it, that we were very lucky to be a part of two peoples, and two long-standing traditions. [They] were sure to tell us that nothing held us back, and we could work to do whatever we wanted to do in the world.”

She added: “I was lucky that not having Asian or multiracial rabbis never made me think it was something that I couldn’t do.”

Asked how she understands her impact as the first Chinese-American rabbi, Mates-Muchin said, “It’s a humbling thing to know that, for some people, their understanding of what’s possible changes based on who their leadership is.”

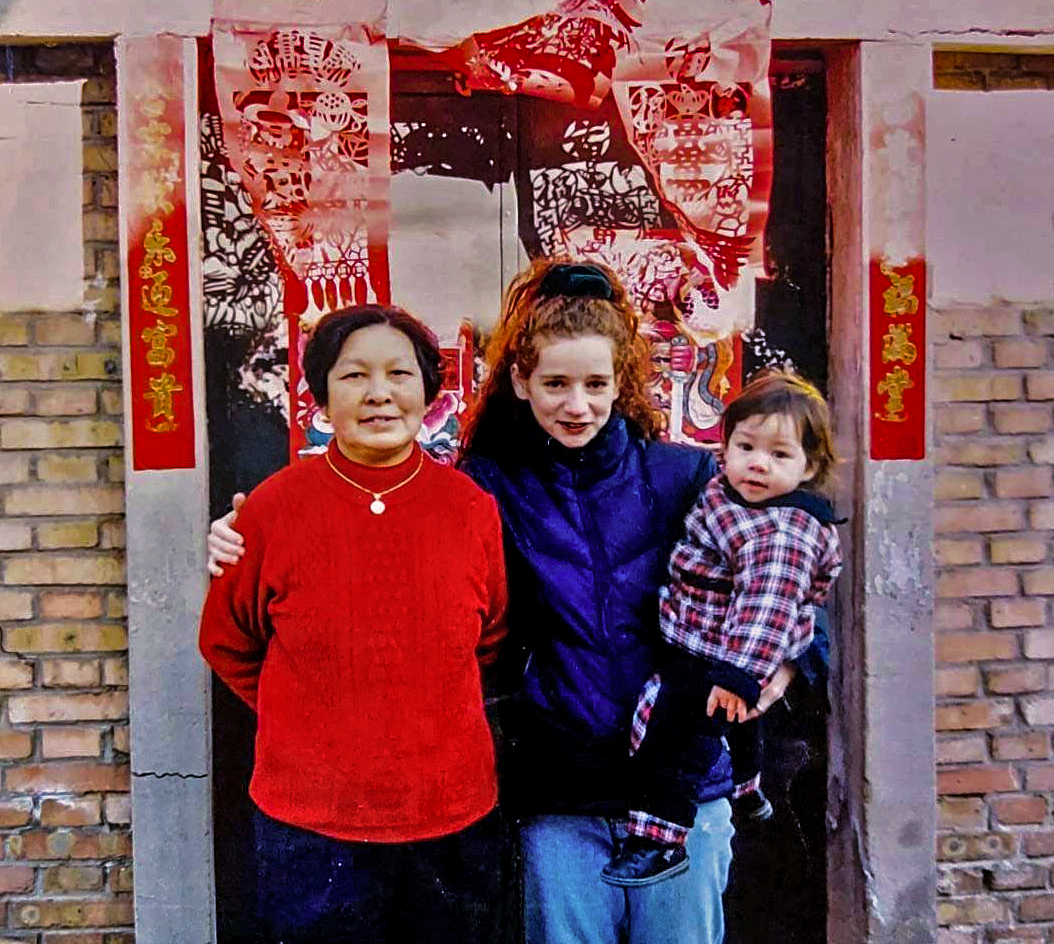

Mates-Muchin (Courtesy)

(I first learned about Mates-Muchin through an event she hosted a few years back called “Chinese and Jewish.” I remember checking the event page, looking at the photo of her, and internalizing for the first time that someone who looks like me and is a mixed Chinese Jew like me could be a Jewish community leader. She was the affirmation I didn’t know I needed until it happened.)

To be sure, as part of a large family and one of the only biracial kids at synagogue, Mates-Muchin definitely stuck out. People often reacted in shock when she told them she was Jewish, or made specific assumptions about who she was based on her race. Some Hebrew school teachers assumed her mother wasn’t Jewish. People also asked her if she was adopted. In college, Hillel leadership assumed she was active only because her boyfriend at the time was Jewish. Despite those experiences, she said she always knew that peoples’ doubts about her identity weren’t about her, specifically, but about internalized biases they held.

“My parents told us very young that people would say those kinds of things,” she said. “Letting us know that that would happen enabled us to recognize why somebody was saying something, and [those things] never made us question ourselves or whether or not we belonged. It would hurt sometimes, of course, but we recognized that they were the ones who were saying something problematic.”

Even so, she said she’s often felt “on the margins” of the communities she is a part of. Outside of her parents’ living room, she said she struggled to find a place where she felt at home. But she believes that being simultaneously an insider and outsider is a quintessentially Jewish experience, one that enhanced her understanding of Jewish history and various communities throughout time. And, once she became a rabbi, that experience inspired her to create a space where people feel they truly belong and can be grounded.

“At the heart of it, we, as Jews, are a people, and we are about belonging and feeling grounded in a people and a tradition that extends as far back as we can remember and into the future as far as we can imagine,” she said. “Some of my experiences growing up taught me the significance of belonging. Being very close to my family, I have a very innate sense of what that belonging is, and when you don’t feel like that.”

Mates-Muchin removes a Torah scroll from the ark at Temple Sinai in Oakland, CA in September 2017. (AP/Noah Berger)

To Mates-Muchin, belonging for Jews of Color means letting go of assumptions and allowing us to tell our stories on our own terms.

“We need to enable the people whose experiences we’re talking about to be the ones who identify when and where and how those things are discussed,” she said. “If the majority of American Jews are able to let go of assumptions and be open to hearing what peoples’ experiences, feelings and traditions actually are, that’s ultimately how community can be created in the most meaningful way.”

One of the assumptions she identified was about the interplay between her Chinese and Jewish identities. In particular, she pushes back against the insinuation that because she is Chinese, her Jewishness would be unrecognizable to non-Asian Jews.

“People think that I must have a Chinese twist on every Jewish tradition, as if we eat fortune cookies instead of hamantaschen,” she said. “It would be as bizarre [to me] to blow the shofar on Chinese New Year as it would be to light firecrackers on Rosh Hashanah. But people expect that my Jewish practice must necessarily be warped because I am also Chinese. Bringing all of myself doesn’t mean that the tradition as it stands has changed. There are aspects to those traditions that are handed down and separate, even as it all resides unified within me.”

Mates-Muchin believes it is important to share our stories about how we interact with our cultures, and in doing so, present a fuller picture of who Jews of Color are. Even though she herself has not always felt welcome in the Jewish community, she also thinks it’s important to highlight experiences that are not just about pain and exclusion.

“I worry that the desire to have this conversation to be more inclusive is swayed to just seeing the experience of Jews who are racial minorities as entirely negative,” she said. “We just need to be open to what people want to share about who they are and how they interact with and have affected the Jewish community.”

Join us online this Friday, February 12, 2021 for a Lunar New Year Kabbalat Shabbat service led by Rabbi Jacqueline Mates-Muchin. [vc_raw_html]JTNDc3R5bGUlM0UlMEElMjNob21lLWxpc3QtY29udGFpbmVyJTIwLndwYl9jb250ZW50X2VsZW1lbnQlMjBibG9ja3F1b3RlJTIwJTdCJTBBJTIwJTIwYmFja2dyb3VuZCUzQSUyMG5vbmUlMjAlMjFpbXBvcnRhbnQlM0IlMEElN0QlMEElMjNob21lLWxpc3QtY29udGFpbmVyJTIwaW1nLnJvdW5kJTIwJTdCJTBBJTIwJTIwYm9yZGVyLXJhZGl1cyUzQSUyMDUwJTI1JTIwJTIxaW1wb3J0YW50JTNCJTBBJTdEJTBBJTNDJTJGc3R5bGUlM0U=[/vc_raw_html]