As the world marks International Holocaust Commemoration Day and the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz this week, I’ve thought a lot about how the legacy of the Holocaust has shaped my commitment to Greek Jewry. I see myself as having a responsibility to the more than 67,000 Greek Jews who perished in the Shoah; not only tell their story, but to ensure that their traditions and customs, my traditions and customs, not only survive, but thrive. Of the nearly 76,000 Jews that lived in Greece before the Holocaust, only 5,500 remain today, and that population is aging. And survivors like Solomon Kofinas have been role models and guides to me my entire life.

Solomon Kofinas, to me, embodies the perseverance I must emulate. If I knew my paternal grandfather, who died long before I was born, I imagine he’d be just like Sol. Born in Athens in 1936, Sol is a Holocaust survivor from Greece. A few years ago, he sat down with my brother to give his testimony of the Shoah. In 1943, three years since the start of the Nazi occupation of Greece, the Germans issued an order that all Jews in Athens needed to go to their local synagogue in order to get kosher rations given out by the Germans. I want to provide you with a brief anecdote from his story that he told when interviewed in 2011:

“One Friday my father took my sister again, they had to go buy food for Shabbat. When they went, my sister never came back. My mother was waiting, she was waiting, my sister never showed up with the groceries. At about 3 o’clock, a young man that jumped the fence of the synagogue, he came over, he knew where the Jews lived. And he was telling everybody ‘the Germans are collecting the Jews. You better get up and leave the house right away.’ So my mother, she didn’t know what to do; it was me, my older brother, and the baby, and she didn’t know where to go. So around the corner from our house, my father used to do business with the tailor, they used to show the shirts that he sold to the businessmen and we asked the man if we could stay at his place for a couple of days until the Germans released my father.

So the tailor said, ‘At night, when I close the shop, get your mattress and come over and sleep here, and in the day you go back to your house.’ So my mother said ‘okay.’ So we stayed there for a week. We slept there.

But on the third or fourth day, she needed some diapers for the baby. She said to my brother ‘hold the baby I’m going back home to get some diapers.’ So she went to the house to get the diapers, and when she arrived there the Gestapo came in and grabbed my mother because they knew, they had the address where we live. My mother got scared; she went under the bed hiding, that’s what the people that lived in our house (the tenants) told us. So she started screaming ‘the baby! The baby!’ So a young boy from the neighborhood heard the commotion and the screaming, and he came over to my brother. He said: ‘your mother is screaming. She wants your baby brother.’ So my brother said ‘here, take the baby to my mother,’ and he grabbed me and we ran away. The other way, far away, away from our home.”

Sol never saw his father, sister, mother, or baby brother ever again. He and his brother fled to the outskirts of Athens, where they hid in various non-Jewish homes before finally reaching his distant family, who he survived in hiding with until the end of the war.

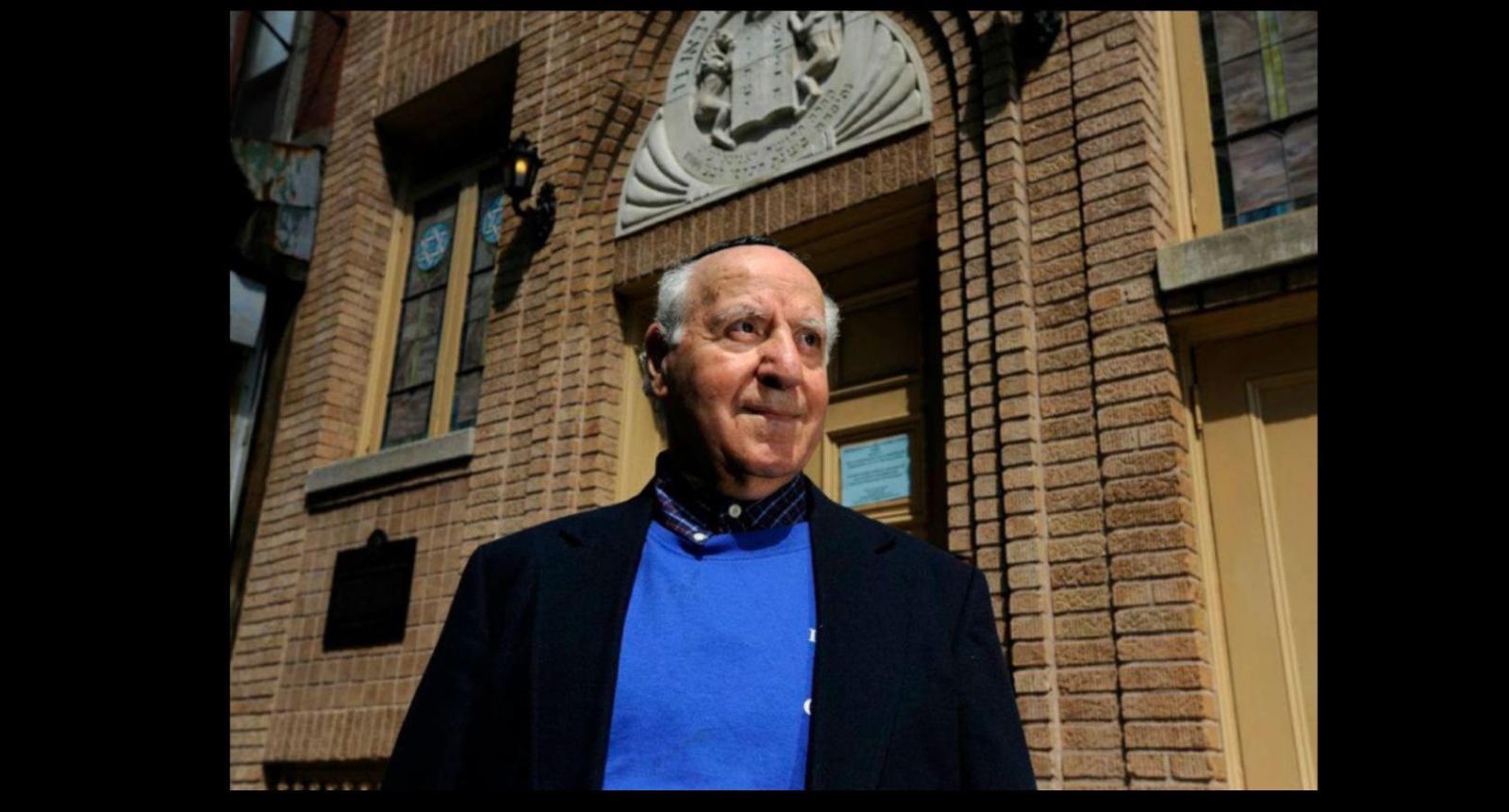

The amount of strength Sol must have had, and still has, is something incredible. That despite almost losing his entire family, he was able to survive the war, go to school, become a mechanic, immigrate to the United States, and start a family of his own, all the while serving Kehila Kedosha Janina and the wider Greek Jewish community in New York City for over 50 years as a Gabbai and lay leader. Today, Sol is not only a father and grandfather but also a great-grandfather.

His strength and story help me continue the fight to keep the Greek Jewish traditions alive. He inspires me, and if I can live up to be half the person he is, I will have lived a truly righteous and good life.

Sol’s story is just one of the many stories of the lost Greek Jewish life. There were so many communities. In the city of Salonica, at the height of the community there were almost 50,000 Jews in the city, over a third of its entire population. The Jewish community was so influential that the main language of art, commerce, and government for decades was Ladino, or Judeo-Spanish. The Jews were so integral to that community that every Friday afternoon, the ports and major shops would close down for Shabbat. This was how it was for “The Jerusalem of the Balkans” until 1943, when the Germans deported over 40,000 Jews to their deaths at Auschwitz. I can speak about the small hill town of Veria where my family was from, and how of the hundreds of Jews that lived there before the war, only a handful returned to their homes in Greece. I can speak about the community in Ioannina, whose history dates in Greece as far as the 1st century CE and where they spoke a unique Judeo-Greco language. Of the nearly 2000 Jews who lived there before the Shoah, less than 40 remain there today. None of these words can do any of these communities justice. Each one, and many others, all had something unique, their own customs and traditions, and individuals with hopes and dreams for their own lives, something I am struggling to help preserve and sustain today.

The Holocaust defines each and every Jew in a different way. To me, it has made me realize how important it is that I not only continue to promote and serve my small Greek Jewish community, but I learn its traditions, minhagim, and love of life that so many Greek Jews did not have the chance to express themselves. These traditions and memories cannot die. For the sake of those lost, I cannot let them die.