Context can change meaning. I wrote this piece just before the events in Charlottesville, VA. Today I am even more deeply aware of the interconnectedness between black and Jewish experiences in the face of injustice, oppression, and racial hatred. Images of young, angry white men wearing swastikas and KKK symbols, holding torches, and chanting, “Jews will not replace us!” and, “Blood and soil!” fill my head and intersperse with those of Civil Rights activists being beaten by white state troopers, and others of Jews being marched to their deaths by S.S. officers aiming rifles at them.

With this new frame, I am asking with new urgency, How will you respond now that history is repeating? How will you fight for justice so that history takes a different course? What kind of world will you leave for your children?

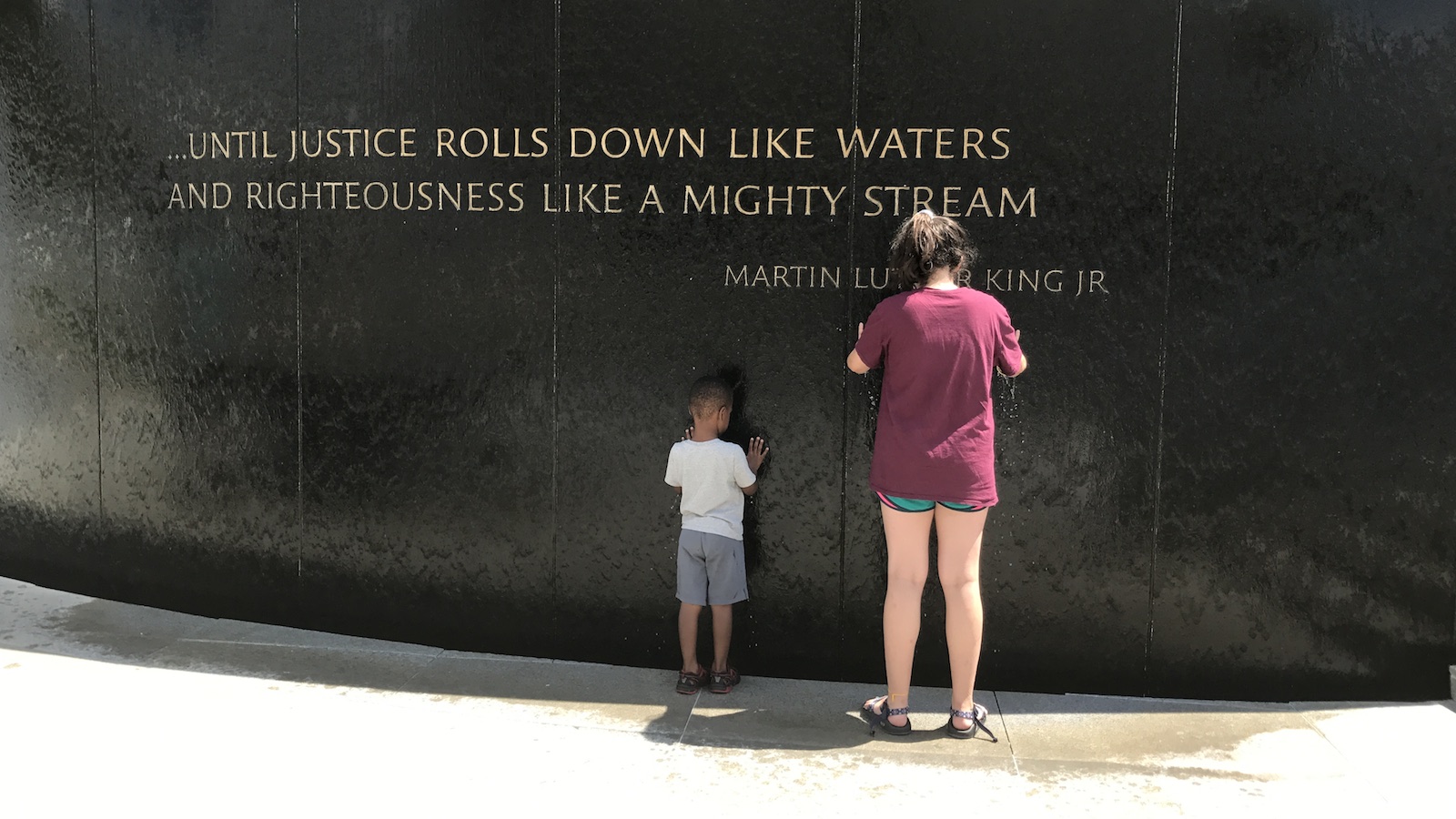

We recently returned from a family trip to Alabama to visit the Civil Rights Trail between Birmingham, Selma and Montgomery. Living in the South, we have touched Civil Rights and the country’s dark history of racial injustice. But I wanted to understand more about my son’s story – about my country’s story. While there, I thought about family stories and heritage, not only related to black American history, slavery and Civil Rights, but also the complicated histories of my family of origin.

I went to the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camps when I was 23 years old. I wouldn’t meet my husband for another five years, but I felt unexpectedly victorious as I walked the tracks into Birkenau, toward the crumbling remains of the crematoria, dreaming of the Jewish man I would one day marry and raise Jewish children with.

Walking those tracks was a powerful vindication to the forces that had tried to exterminate my people. I was alive, two generations later, and my line would continue. I married a man whose family were also survivors, from a town 30 kilometers from Lodz, Poland, where my family had lived for generations.

Unraveling the untold stories of my family and returning to the places where they had lived and so many had died was cathartic and healing. It was also infuriating and disheartening; I could never recover what had been lost. I saw the way the Holocaust had inflicted a sharp and jagged crack in my family, one that has become a profound part of its legacy and still impacts who we are.

What I didn’t know that day in Birkenau was that I would, almost 20 years later, adopt a black son. And the crack of my family story would intersect with the crack of his own history – one he is still, at age four, too young to comprehend.

Back from Alabama, I am filled with images of the Civil Rights sites we just visited and the stories we heard. The juxtaposition of Civil Rights and Civil War that is ever present in the South – Confederate flags honoring fallen soldiers in cemeteries, monuments to Confederate heroes of the struggle for “states’ rights” – the right to own other humans. Heroes who would become leaders of the KKK.

This image remains with me: We are in the 1800s ghost town of Cahawba. Fallen houses remain, one inhabited until 1995 by a descendant of slaves. The slave quarters of a now-erased mansion. We make our way to the slave cemetery and follow the paper guide to ten graves marked with numbers and stones. There are hundreds of other unmarked graves where people whose skin is brown like my son’s rest.

My son runs ahead looking for the next marker. My black son whose ancestors were abducted from their people and brought over on slave ships; sold at auction, enslaved. My black son, whose history I can only imagine, grasped for the first time in Alabama that black people – his people – were once slaves like the Jews in Egypt. This is his entry into understanding slavery, because in Jewish preschool at Passover he has learned the story of Moses and Pharaoh.

I wonder about those who came before him like I did about my own ancestors. Our cracked histories intersect shared experience of violation, murder, genocide, a history and people exterminated. But our stories are different: The violation against his people didn’t stop when slavery ended or when Jim Crow was outlawed. It didn’t end with the Voting Rights Act, which is being unravelled today, or when schools were integrated, schools that are resegregating today. It didn’t stop when a black man became president. The violation against his people takes different forms; racial discrimination is alive and well. These are the stories of his heritage and the reality of his present that I have a responsibility to explain to him as he grows older.

How do I tell those stories in a way that instils hope?

I am the white Jewish mother of a black Jewish son. My ancestral story, my ancestors, will become his only if he chooses them. But even if he does, he has another critical story. His ancestral story is a different one than mine. His roots originate in a different part of the world, his path winds through other places in ways I can never claim to completely understand.

I want to give my son heroes. I want to give him ancestors, but I know so little about his roots that I can only put pieces together from a broader, painful story. I want to give him community, a sense of belonging to his own people – both black and Jewish.

I want to give him his own story, but I know it will be his to write, his to tell, and his to claim.

A longer version of this piece and more of Gal Adam Spinrad’s writing can be found here.